Personal Structures – Crossing Borders: Palazzo Mora, Venice

Object - Lamp, 2015

Inkjet print on archival Hahnemuhle cotton rag

100 x 70 cm & 140 x 99 cm

Object - Table, 2015

Inkjet print on archival Hahnemuhle cotton rag

100 x 70 cm & 140 x 99 cm

Object - Vase, 2015

Inkjet print on archival Hahnemuhle cotton rag

100 x 140 cm & 140 x 200 cm

Object - Footstool, 2015

Inkjet print on archival Hahnemuhle cotton rag

100 x 70 cm & 140 x 99 cm

Object - Ashtray, 2015

Inkjet print on archival Hahnemuhle cotton rag

100 x 70 cm & 140 x 99 cm

0.00

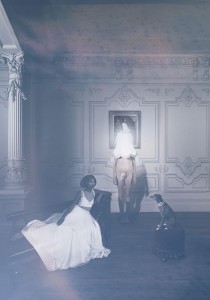

Object - Lampshade, Table, Vase, Footstool, Ashtray, 2015

Inkjet prints on archival Hahnemuhle cotton rag

Installation View

Michael Cook

9 May - 22 Nov 2015

Michael Cook

Personal Structures: Crossing Borders

Palazzo Mora, Venice

Vernissage 7 – 8 May 2015

Personal Structures runs from:

9 May – 22 November 2015

Michael Cook’s photographic tableau seduces with its aesthetic, and a black and white tone made radiant with a suffusion of barely visible colour. Placed in a luxurious drawing room, these unfolding scenes of beautifully dressed black people in period costume set up a contradiction, a shock within such civilised interiors, with the naked white person amongst them who becomes, variously a lamp, a table, a vase, a stool and an ashtray. Object takes a reversal to depict historic interracial inhumanity once routinely practised – a black person “owned” by a white – and drives home the depravity of carelessly treating people like objects. This is, arguably, Cook’s strongest series yet in a developing oeuvre that has brought him critical acclaim.

The centrepiece of this series is the largest image, Vase. It shows a choreographed arrangement with multiple images of the same beautiful black Lady, elegantly dressed in fashions to suit the period of the house, hair elegantly coiffed. At the back of the room is her Lord, also in ornate period dress, white tights and tails that emphasise his blackness. The “Vase” is central in the room, her nakedness obscured by the large bunch of Australian native flowers she holds aloft. The Australian natives are a neat and witty reversal of the notion of the indigenous and represent the exotic otherness so sought after by explorers of the colonial period. Her ankle is tagged with string and a label reading “VASE”, akin to a price tag for a slave going to auction in the style of advertisements in newspapers from the 1800s. Paintings on the back wall add to the symmetry of the arrangement, and echo the “decorator” status of the naked “Vase”.

This tableau moves across the images, unfolding languidly reflecting the leisurely indolence and boredom of the lives depicted here. It opens in the Lady’s dressing room, with a “Lamp” standing in front of a photographic portrait of a young African slave named Sarah Forbes Bonetta, who was gifted to Queen Victoria in about 1850. Her eye meets the viewer intelligently, yet her inclusion notes the objectification – her person gifted and passed parcel-like from country to country. The dog sits on the footstool wearing an ornate collar, reinforcing its pampered status and the owner’s largesse and charity – to animals. In Table the back wall features a painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761-1804), whose story was fictionalised in the movie Belle (2014). Born to a slave mother in the West Indies, her father was English naval officer Captain John Lindsay, who took her to his uncle, Lord William Murray, Earl of Mansfield, within whose household she was raised as an equal with another niece, Elizabeth Murray. In the painting, attributed to Johann Zoffany, c.1778, they stand together, in clothing that denotes their equal status, Elizabeth reaching affectionately for Dido. The recreation of this portrait on the back wall refers to the influence of Lord Mansfield who, as Lord Chief Justice, handed down a judgement which led to the ultimate outlawing of slavery in the United Kingdom in 1772.

The dynamic across the series of images is filmic. The Lady moves between images two and three, the man exits Vase and is seen in his drawing room in Stool. Relaxing with his dog on the couch, he rests his stockinged legs casually on a naked woman who kneels on the floor in front of him. On the back wall is a painting of Christ on the cross, which makes a point of the disjunction between the ethics and the practice of Christianity and, on the left, is a portrait of King George IV, who was king when Captain Cook embarked for Australia. Ashtray, too, sees the lord of the manor posing with his cigar above the naked ashtray and averting his eyes – from her and the viewer alike. The woman’s head is thrown back, echoing the agony of Christ in Michelangelo’s Pieta (St Peter’s, 1498-99), and the dog echoes the indifference of its master, sniffing at her feet. These images are demeaning, the naked presentation of the human “objects” denoting an associated “uncivilised” status. Their depiction, within an historic setting, allows an ethical distance for their audience, yet in their objectification of race they note the ongoing discriminatory issues that plague humanity the world over.

– Louise Martin-Chew