IN THE GALLERY: The Return

Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge Returning to its Manly Birthplace, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

245 x 183 cm

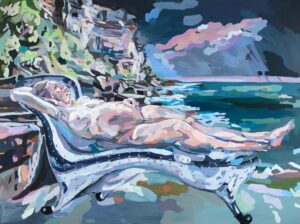

Reclining Allegory on Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge at North Head, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

245 x 183 cm

The Return, 2024

Installation View

Photo: Simon Strong

The Return, 2024

Installation View

Photo: Simon Strong

The Return, 2024

Installation View

Photo: Simon Strong

Ultra-durable (Sebel Integra Chair Set), 2024

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 183 cm

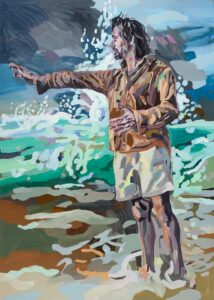

Self Portrait of the Artist as Demosthenes, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 152 cm

Cape Pillar And The Albatross, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

121 x 152 cm

The Return, 2024

Installation View

Photo: Simon Strong

The Return, 2024

Installation View

Photo: Simon Strong

The Return, 2024

Bligh Street Storm Front #2, 2023

Acrylic on canvas

245 x 183 cm

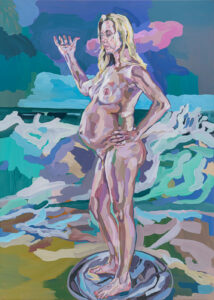

Allegory of Rhetoric on SANAA Drop Chair, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 152 cm

Photo: Simon Strong

Rogue Wave, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 183 cm

Sweet is the Swamp #2, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

152 x 183 cm

The Return, 2024

Photo: Simon Strong

The Return, 2024

Photo: Simon Strong

The Return, 2024

Photo: Simon Strong

The Return, 2024

Photo: Simon Strong

Oliver Watts

22 Aug - 7 Sep 2024

There is no such thing as a singularly contemporary painting style. Our world has become too big and our arts movements too fractured, for us to designate any one style of painting as more contemporary—more of our moment—than another. It’s a ridiculous thing to claim. Yet despite this ridiculousness, there is something unmistakably singular and contemporary in Oliver Watts’ new series: The Return. Maybe, it’s in his slashes of paint, which slide between abstract facture and descriptive form. Maybe, it’s his compressed palette, or his handling of acrylic paint, which feels at once utilitarian and sumptuous. I’m not sure, but it’s there.

Watts’ works offer more than mere statements of their own contemporariness, however. Within his paintings, the past and the present collide. We see the past rear its head most conspicuously in the form of his subjects. Watts is obviously a student of history. Although, perhaps, it is better to say that he is a critical observer of the past—a student of history is too staid in their interpretations, too unwavering in their acceptance. In Watts’ hands, the past is conversely mutable; it offers up the possibility of play and reanimation. It is a place to explore new stories, not just repeat old ones.

The classical idea of speech and civic discourse is clearly front of mind in Self Portrait of the Artist as Demosthenes (2024). The title recalls the fourth-century BC Athenian orator, Demosthenes, who famously overcame speech impediments by putting stones in his mouth and practising his speeches beside the ocean, projecting his voice over the roar of the sea. In self-styling as this classical figure, Watts draws to the fore the difficulty of speaking, and, more than that, of being heard today. The stance of Watts’ figure borrows from an 1859 depiction of Demosthenes by Eugène Delacroix. There is something of the nineteenth-century French artist’s Romanticism in Watts’ painting, which not only retains the earlier work’s dramatic gesture but also some of its windswept heroism. Yet while in Delacroix’s painting the waves are small and visibly overcome by Demosthenes’ voice, the outcome of Watts’ painting is less clear. Here, water sprays into the air, and the pictured figure almost seems on the cusp of immersion, as if he could be swept away at any moment. One senses an idealism at play here, but equally the limits of this ideal.

In Allegory of Rhetoric on SANAA Drop Chair (2024), the artist, at first glance, again seems to transact in convention. Here, Watts presents a nude figure in a classical stance, with the basic composition recalling something of Botticelli’s iconic Birth of Venus (1485-1486). Yet look closer and this commitment to the past begins to waver and slip into something far more unique. Watts’ figure is, in fact, standing astride a SANAA Drop Chair—the kind of unmistakably cool furniture piece that one expects to find in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, rather than a coastal landscape painting. Confronted with this incongruity, one is pressed to ask what the conditions for speech are today? Whether this figure—which the artwork’s title identifies as the “allegory of rhetoric”—can literally only be platformed if she stands astride this chair? Is this the soapbox of twenty-first century commodity culture: shiny, silver, effortlessly chic, and only available at auction?

This interplay between cultural heritage and consumer fetish, perhaps, finds strongest expression in Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge Returning to its Manly Birthplace (2024). Here Watts has replaced the painting’s human protagonist with Newson’s iconic furniture design. Within the cultural imagination, Newson’s lounge has largely become uncoupled from the place of its conception. Watts’ painting playfully places the iconic furniture on the coastal cliffs of North Head, satirising the triumphant return of the piece to Manly—in a painted gesture that critically suggests the pull of cultural provincialism, and the false promise of transcendence and utopic internationalism. Newson’s lounge sits in both worlds.

In Ultra-durable (Sebel Integra Chair Set) (2024), we see a humble domestic setting. Here is a brown table surrounded by a set of six chairs. The scene is filled with memories: the chairs are something from the painter’s childhood, which predate his birth, and were given to his mother by the Sebels, who were also part of the Australian Jewish diaspora. The furniture is in this sense autobiographical. Yet it is also the world’s first single-piece moulded polypropylene chair—an Australian-made icon of sorts, which, as the artist notes, has gone on to become a permanent fixture of American prisons. The advertising for the chair foregrounds this ubiquity: “Unrivalled in strength and durability, the Integra has been the chair of choice for leisure centres, prisons, institutional facilities, schools, universities, churches, community halls, recreational and sporting applications as well as alfresco dining.” Again, Watts plays a multidimensional game here, as his painting supports an ostensibly clear narrative—one which is rose-coloured and nostalgic—yet also undercuts this easy reading, with a darker more existentially-riven reality. It is two worlds contained in one fire-retardant chair.

-Words by Tai Mitsuji

Artist Drinks: Sat 31 Aug | 2 – 4pm