TESTAMENT PT.XXXXXXVIII

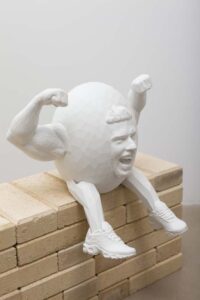

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

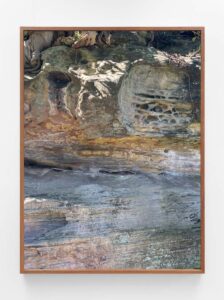

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

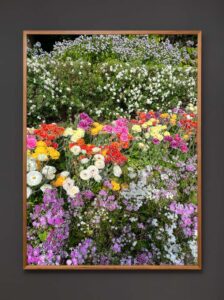

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

Installation view of 'TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII'

Installation View Stanley St. Gallery, East Sydney, October 2020.

Image Credit: Docqment.

Jackson Farley

28 Oct - 12 Nov 2020

There’s a kind of innocence and earnestness to looking up at the clouds. It’s something we do as children – searching for shapes, glimpses of meaning that might suddenly give form to the expansive and changing sky. This yearning to explore and make sense of our world is lost as we grow. When we’re not looking down, we look up and feel suddenly small, distant to whatever lays beyond and at the same time, completely at its mercy.

It’s this notion of the sublime that Jackson Farley uses as the backdrop to his work, but rather than surrendering to these systems of value at play, he peers through – poking and prodding, making fun and inserting his own narrative.

His images, taken on his iPhone and blown up to 17 times scale are riddled with Jackson’s mark making; zany loose drawings overlay the forms of clouds, rock faces and flowers and he uses text to give voice to the anecdotes and narratives at the heart of each work. Whether it’s ‘i miss you’ sprawled out over the heavens or lyrics to Taylor Swifts ‘We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together’ tagged onto “Jesus’ tomb”, each mark becomes a catharsis and speaks to a kind of universal history – a mourning for naivety, lost love and family departed.

In Jackson’s video work, which shares the exhibition’s title, we see a tangible 69th edit of the Bible. The Old and New Testaments are collaged together with the artist’s personal narrative to create a hypnotic world that embellishes the fantastical nature of the original text. The crucifix that Jesus died on finds its voice and “naughty” escapades ensue in the party to end all parties; where the faithful are turned into “techno fish” and father and son finally have that much needed talk.

Using irony, afforded by combining seemingly ‘pure’ and ‘impure’ imagery and text, Jackson channels the subliminal and parodies the way in which we see ourselves and our world. With the crudeness of slapstick, schoolboy humour and sexual innuendo, this body of work speaks to the irony of religion, god and notions thereof, whilst also conversely, being just as sentimental, heart-felt and self-reflective.

In many ways, TESTAMENT PT. XXXXXXVIIII plays with value: we search for identifiable shapes in the clouds, find ourselves in the lyrics of Taylor Swift songs and we cannot help but identify the number 69 with oral sex. These dualisms almost appear as compulsions, competing for primacy within the spaces of image and video, one sitting alongside the other. They speak to the pathos and hierarchy of Catholicism, whilst also pointing out its irrevocable contradictions.

Words by Emma Pinsent