Art Basel Hong Kong 2014

Acacia, 2013

oil on wood

10x15cm

Aster, 2013

oil on wood

6x8cm

Camellia, 2013

oil on wood

15x20cm

Carnation, 2013

oil on wood

5.5x8cm

Clover, 2014

oil on wood

15x20cm

Flora, 2013

oil on wood

10x15cm

Gardenia, 2014

oil on wod

6x8cm

0.00

Helenium, 2014

oil on wood

4x5cm

0.00

Iris, 2013

oil on wood

4x5cm

0.00

Juniper, 2014

oil on wood

4x5cm

0.00

Lotus, 2013

oil on wood

5.5x8cm

Marguerite, 2013

oil on wood

10x15cm

Oleander, 2014

oil on wood

15x20cm

Peony, 2013

oil on wood

10x15cm

Natasha Bieniek

1 - 31 Mar 2014

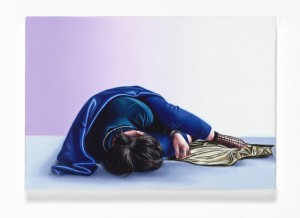

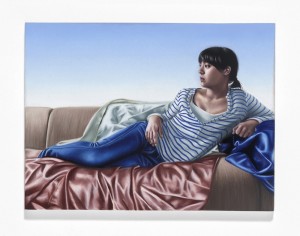

We live in a culture consumed by digital media. More than ever, we use images to facilitate our need to connect and communicate with the outside world. Social networking sites enable us to share a part of ourselves in a deciphered way. Sometimes this is an honest interpretation but often we can create a fabricated version of our existence. Addicted to our technological devices such as smart phones, we can become lost and overwhelmed in the current trend of constant portraiture never-ending streams of “selfies” on our Instagram and Facebook news feeds.

These technological devices and applications miniaturise and manipulate the way we regularly look at pictures, and this is also inherently common when it comes to portrait painting. Natasha Bieniek’s new series shares this link between how we perceive images in contemporary culture and how we have done so in the past.

When we think of historical painting we tend to instantly think of large paintings, profound masterpieces of a considerable grandeur, but during the 16th century another kind of painting became significant: the miniature portrait. These portraits were portable, often resembling medals or pendants and used as keepsakes when one travelled or were away from loved ones. These treasured images served a similar purpose as today’s ‘camera roll’ on our smart-phones. The physical nature of Bieniek’s work aims to mirror the form of a modern technological device composed at the same sizes as smart phones and tablet screens, her paintings scale and glossy surfaces reflect the way we often view images. Due to her paintings small proportions, the normal physical space between the viewer and the work is forcibly narrowed, emphasising the nature of today’s image culture and audience connectivity.

In terms of subject matter, Bieniek’s work is also inspired by classical gestures commonly seen in traditional painting. A raised finger is used to symbolise religious beliefs or to lead the viewer’s attention to a certain point. Bieniek’s work aims to direct the focus back to the individual, encouraging the theme of self-portrayal and the widespread exposure of our own image through contemporary technology.

Although Bieniek’s work is traditional in its approach, there is a strong correlation with contemporary working methods and image-viewing. Images are composed digitally and then edited extensively. Computer generated gradient fades are seen within the backgrounds of her work to symbolise this process. Fundamentally, Bieniek’s work aims to demonstrate a juncture between proximity, intimacy, tradition and contemporary culture.