IN THE GALLERY: Catharsis

Catharsis, 2020

Catharsis, 2020

Catharsis, 2020

Catharsis, 2020

Catharsis, 2020

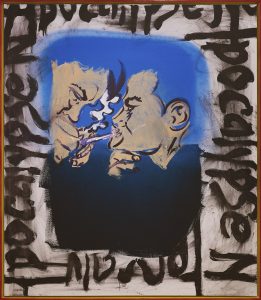

Untitled 1, 2020

Synthetic polymer paint, pastel, oil on canvas

150 x 130cm

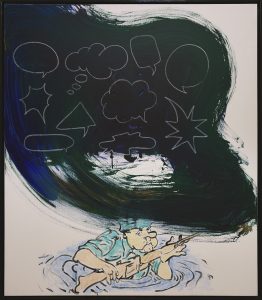

Untitled 2, 2020

Synthetic polymer paint, pastel, oil on canvas

150 x 130cm

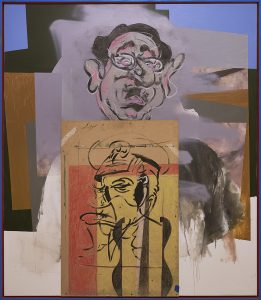

Untitled 3, 2020

Synthetic polymer paint, pastel, oil on canvas

150 x 130cm

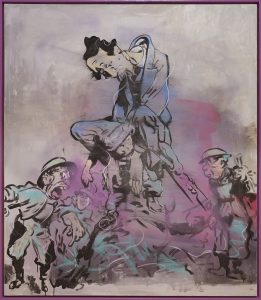

Untitled 4, 2020

Synthetic polymer paint, pastel, oil on canvas

150 x 130cm

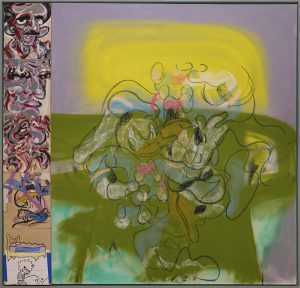

Untitled 5, 2020

Synthetic polymer paint, pastel, oil on canvas & board

150 x 150cm

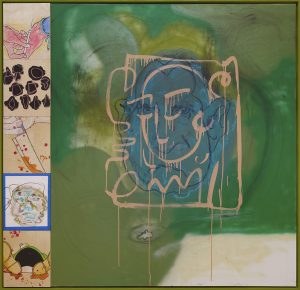

Untitled 6, 2020

Synthetic polymer paint, pastel, oil on canvas & board

150 x 150cm

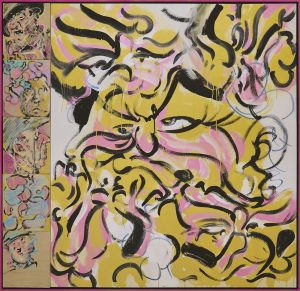

Untitled 7, 2020

Synthetic polymer paint, pastel, oil on canvas & board

150 x 150cm

Benjamin Aitken

4 - 25 Nov 2020

It should come as little surprise, to anyone who knows him, that Ben Aitken was something of a scallywag and rascal as a youth, prone to either cause, or become embroiled in, all kinds of strife and mayhem. His father, a somewhat strict military man, recognised this early on and, rather than watch his teenage son be hauled off to jail, suggested that perhaps he would enjoy enrolling in the armed forces. The young Aitken, bubbling with testosterone, and having grown up with stories of his grandfather’s exploits in war-torn Vietnam, thought this to be quite a grand idea – AK47s and Chinook helicopters – hell yeah! However, his mother, having stumbled upon this father-son plot, put a quick stop to such wild-boy fantasies. Ben should pursue his artistic side, she proclaimed. The conversation stopped there.

Ben Aitken would have made quite a questionable soldier. Perhaps in late ’60s Vietnam he would have ‘fitted in.’ A substantial percentage of the military at that time were conscripts and certainly lacking the training of contemporary military life – a fact which, of course, led to some of the more hideous missteps of that particular conflict. Booze and drugs, especially heroin, were ubiquitous. Aitken was far too young to have experienced his grandfather’s Asian misadventures, but he was old enough to smell the napalm of its incendiary cultural outpourings, namely such moments as the neon noir of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Oliver Stone’s Platoon and Michael Herr’s stunning new journalism in Dispatches. And somehow drugs and booze fed their way into the young artists’ own life.

This show is aptly titled Catharsis – referencing both a terminology used for heroin addicts and slang for the disastrous confrontations between the Vietnamese and the ANZACS – shooting up (smack) and shooting up (civilians). This is a show of both catharsis and reminiscence. Violence nudges gratingly against humour. There are hints of his Great-Grandfather’s murder during a fight with American troops on Brett’s Wharf in Queensland during the Second World War and the ironies of Disney figures recreated ss savage bomb-squadron logos on bomber planes.

Here Aitken has appropriated, reworked and recontextualised cartoons and caricatures from the Vietnam conflict to chilling effect – not avoiding the racial visual slurs toward figures ranging from Ho Chi Minh to Henry Kissinger. This is a body of work that embraces its own catharsis in vibrant colours and gestural mayhem – the narrative of Aitken’s upbringing in a military family, boxing, substance abuse and discipline which has formed his work ethic within the art world. –Ashley Crawford