IN THE GALLERY: Sweet is the Swamp

Sweet is the Swamp, instal view

Sweet is the Swamp, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 183cm

Paperbark Swamp (Centennial Park), 2021

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213cm

Lachlan Swamp, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213cm

Sweet is the Swamp, instal view

The Ibis Wading (after Nolan), 2021

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213cm

Sweet is the Swamp, instal view

The Thorn, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213cm

Paperbark Swamp, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213cm

Paperbark Swamp (Waterlillies), 2021

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213cm

Sweet is the Swamp, instal view

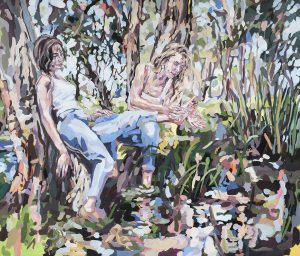

Camille in the Swamp, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213cm

Sweet Is The Swamp, 2021, instal view

Lachlan Swamp 2, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

91 x 121cm

Sweet is the Swamp, instal view

Paperbark Swamp Lillies 2, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

91 x 121cm

Sweet is the Swamp, instal view

The Thorn 2, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

91 x 121cm

Elle in the Rain, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

91 x 121cm

Sweet is the Swamp, instal view

Oliver Watts

21 Jul - 14 Aug 2021

In the early hours of December 28, 1803, the escaped convict William Buckley stopped to breathe after a night on the run. His hair was streaked with mud, his penal uniform in tatters, and he had a large gash on the bottom of his left foot, having lost a shoe behind him in the scrub. Along with three others, Buckley had escaped the new settlement at Sullivan Bay, near Port Phillip, in Victoria, having arrived on the HMS Calcutta from Portsmouth earlier that year. But he was alone now, having split from his companions. The mosquitoes were bad, but worst of all was his hunger. Moving slow among the bark, he hoped for a fish, or maybe a frog. But as he knelt by the water, the light shifted. Seconds later, a bunyip rose slowly from the swamp. Buckley stood up and watched as the strange creature moved towards him. It was the size of a calf with a blue beak and eyes that blinked from beneath dusky feathers. When the convict called out for the creature to stop, the bunyip disappeared. Almost fifty years later, Buckley, who was illiterate, told this story to John Morgan, who published it in The Life and Adventures of William Buckley. Asked what happened after he’d seen the bunyip, Buckley said, “It started to rain.”

I thought of this bunyip sighting when I saw Oliver Watts’ painting, ‘Elle in the Rain, as part of the exhibition Sweet is the Swamp, currently showing at THIS IS NO FANTASY. A naked woman stands in a rain shower, her feet sunk in mud, her face angled to catch the drops. Although there is no bunyip, the way in which the green seeps into the darker colours of the water had me asking if this couldn’t be a scene similar to Buckley’s encounter? Like so many reports of bunyip sightings in the nineteenth century by European settlers, the creature is fleeting. Something has disappeared. The water is troubled. Blink and you will miss it. Perhaps it was never there at all.

The works in this show, which build on Watts’ exploration of landscape in previous exhibitions, The Retreat and Autopilot Steering, give a palpable sense of the light, the heat and the scent that attends the Australian interior. They take you along a dusty track, at noon, only to descend into the wetland and become disoriented by the dark greens and grey-browns of the foliage. Shades of blue peek in from the bushland canopy, but the traveller isn’t sure if it’s the sky or the trick of reflections on the ferns. The large scale of ‘Lachlan Swamp’ and ‘Paperbark Swamp’ ask you to shed the ageing pair of hiking boots and step inside. Go barefoot, like William Buckley. Tell his ghost to leave some food for the living. Dragonflies and nesting birds are almost audible, and it is possible to take up residence on a fallen log or dry patch of flowers and wait for the senses to reorient. Forget dinner, and the return to camp. Wait long enough and you’ll meet others, like in ‘The Thorn’, where two young women — the artist’s friends Camille Klose and Elle Charalambu — rest among the bark, one of them attending to a splinter. The women may have sore feet, but they show no fear of mosquitoes or bunyips. They are apparitions, true creatures of the swamp.

Not long now. It’s time for a swim, as in ‘The Ibis Wading (After Nolan)’, perhaps the finest painting of the series. One of the women, inspired by the heat, has turned from her companion, disrobed, and entered the water, only to be joined by a bird. The work owes a debt to Sidney Nolan’s long-running series, ‘Leda and the Swan,’ painted during the 1940s-60s and inspired by Yeats’ poem of the same name. Like Nolan’s work, the nude here is faceless, seemingly lost to the vastness of the interior, and yet, more intimate. The figure’s anonymity allows the viewer to join the water, cool off in the lilies. There will be no trespass, or rebuke, because the figure is someone the viewer knows. Not Camille or Elle, but a projected body, like Greek mythology’s own Leda, who, as in Nolan, has her back to us, leading us out. Nolan’s swan, according to the legend, is inhabited by Zeus, and the ibis, too, is no mere scavenger, but a potential suitor and guardian. In swapping out the swan for the ibis, Watts updates Nolan without the need to rely directly on myth. The common bird is a nosier, and thus, friendlier companion, and would plausibly accompany a swimmer off the track.

Why are these works ultimately so powerful? Form is everything. Watts’ careful brushstrokes, seemingly sporadic, are the result of painful deliberation, simultaneously building up, and obscuring, the landscape. There are parts of these works that appear as smaller abstractions, placed side-by-side, like jigsaw pieces (only with liquid edges). I imagine it would be possible to cut sections out with a clean scalpel and still get a sense of the exquisite layering and control. The colour palette is muted, sun-kissed, and yet feverishly alive, a contradiction that adds to their sense of mystery. Many landscape paintings refuse to be looked at again, offering little more than lazy realism or spotty kitsch. But these works are different. The eye is drawn back, and not just because of their scale, but because they invite. They want to collaborate, and change shape. We see the paperbark and then it shifts. We see the figures, until they too, shift.

In all their beauty, these works also offer a guide to art history, Australian mythology, postcolonialism, and a reminder you don’t need psychoactive plants to hallucinate in the bush. Just walk further into the wetland, circle the rim of one swamp, and the next, and go easy among the darters and ibises and the occasional nude. Sweet is the Swamp is clear evidence that Watts is one of the country’s most exciting and inventive contemporary painters.

– Nathan Dunne

Click here for an interview with Oliver Watts in Art Almanac