IN THE GALLERY: GRAVITY

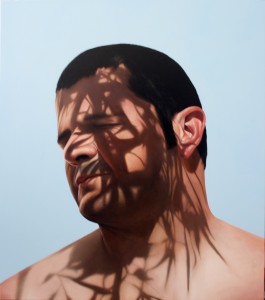

The Twist, 2008

Oil on linen

122 x 107 cm

A Glitch in the System, 2008

Oil on linen

122 x 183 cm

From Grave to Cradle, 2008

Oil on linen

122 x 107 cm

An Orbit's Conclusion, 2008

Oil on linen

50 x 40 cm

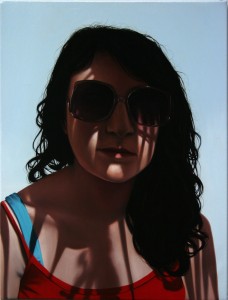

Inversion, 2008

Oil on linen

122 x 107 cm

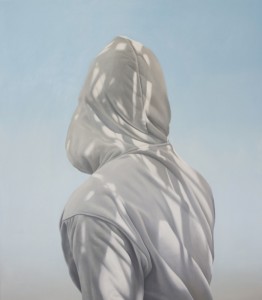

An Imminent Silhouette, 2008

Oil on linen

66 x 51 cm

Juan Ford

1 Dec 2008

Wake in Fright

Tread softly. Juan Ford’s people are lost in troubled sleep. Shadows fall about their face and twitches of irritation pulsate the corners of their eyes. The leaves that form the shadows are eucalypt; unmistakable Australians whose tendril shapes immediately evoke their smell. And with it the feel of a hot, hot sun which burnishes the soul. Feeling hot, and getting hotter. Above, wheeling ‘round the skies like a bleach-white mock of a crow, flies the skull in whose teeth these leaves are clenched. An ominous portent who casts them shadows, this Antipodean Grim Reaper in all its triumphant glory.

Grinning skulls. Sharp white light. The mirage-like shade of a gum tree, which obscures but does not cool. An unnerving clarity of detail where none may really hide. These are motifs of great familiarity to Australians and our tales of early exploration are full of them. Particularly the symbols of death. Of fools who pitted themselves against the environment believing they could impose their will upon it. Who perished praising Empire. Who perished damning God. Who returned to gleaming bone amongst stray bits of leather, metal and camel. Who returned from whence they came. Dust to dust. And still the land lived on.

Juan Ford’s paintings are reminders, contemporary vanitas that implore: ‘Wake up, ye troubled sleepers, for the shadows are already cast.’ In the face of human rapacity, cupidity and stupidity, the environment is finally fighting back. The shadows we once cast upon the land are now cast upon us, like sardonic vegetal corpse paint, that make-up so beloved by Death Metal bands. With an artist’s eye forensic and meticulous, Ford treads the tightrope between faithful reproduction and psychological tremor, referencing photography but moving beyond photo-realism. Every detail is in-focus, creating an unnatural (and unsettling) depth of field which both fascinates and jars. He deliberately aims for the seductive recognising that the longer one looks at a painting, the more the viewer becomes self-reflexive: “Sometimes this can be a twist of the knife or a tap on the shoulder, (a reminder that) we are mortal.”1

Whilst this may appear a tad self-righteous, it’s a theme which has been running through Ford’s work for more than a decade. From the Romanticist suburban roof sunsets of the late 90s, through isolated souls projecting their (unfulfilled) desires in the early 2000s, to the awful splendour of atomic blasts or the reflection of a glass half-full, Ford has sought ways to portray the impulses that are important for him via an ever-evolving technique rooted firmly in the language of paint. Consider, for example, A Glitch in the System, where a dazzle of red pills scatter through the leaves. Pragmatically, it is a simple colour theory solution making the reds and greens vibrate optically, which simultaneously magnifies the “weird, unreal sensibility” whilst fragmenting the depth of field. At the same time, Ford remains firmly on message, conjuring “an absurd human solution to any problem. Throw a bunch of pills at a tree… But that’s kinda what we’re doing with the environment.”

Complicit with this knowledge, Ford’s people slumber on, lulled low by the noon-day sun. With eyes shadowed, closed or concealed, thoughts flicker ‘cross their brows. Unnoticed, we engage in abject scrutiny.

Of ourselves.

Andrew Gaynor