IN THE GALLERY: At Redleaf

At Redleaf, 2022

Installation View

Photography © Janelle Low

At Redleaf, 2022

Installation View

Photography © Janelle Low

At Redleaf, 2022

Installation View

Photography © Janelle Low

Sappho on the Cliff at Redleaf, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213 cm

North Head (Boree) in a Storm after Conrad Martens, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 244 cm

Redleaf through a Pine Tree, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213 cm

At Redleaf, 2022

Installation View

Photography © Janelle Low

At Redleaf, 2022

Installation View

Photography © Janelle Low

At Redleaf, 2022

Installation View

Photography © Janelle Low

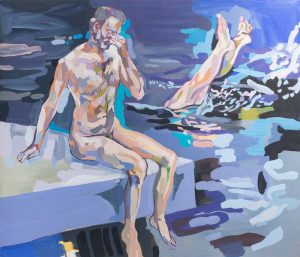

Daedalus on the Pontoon at Redleaf, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213 cm

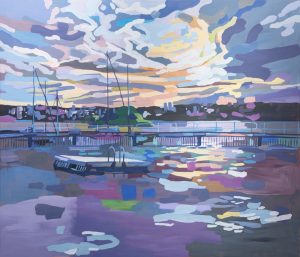

Redleaf at Dusk, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 244 cm

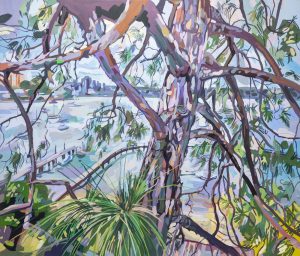

The Fig Tree, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213 cm

The Pontoon at Night, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

183 x 213 cm

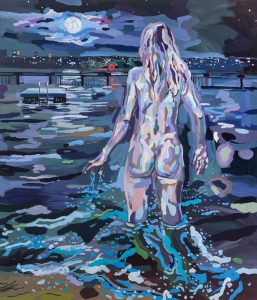

Phosphorescence [alt. Night Swim], 2022

Acrylic on canvas

213 x 183 cm

At Redleaf, 2022

Installation View

Photography © Janelle Low

Oliver Watts

1 - 25 Feb 2023

“He looked down the slope and, at the base, in the shadow of the wall of the Park, he saw some human figures lying. Those venal and furtive loves filled him with despair. He gnawed the rectitude of his life; he felt that he had been outcast from life’s feast.”

– James Joyce, ‘A Painful Case’, from Dubliners

The idea that Sydney has “secret beaches” at first seems unconvincing, one of those harmless media fictions which announce the arrival of summer. How can any secret be mapped, accessible, and so crowded on a hot day? But the description hints at something true, because along the shoreline of the largest natural harbour in the world is a real, liminal double city. Very few locals know that Port Jackson holds as many as sixty beaches, or how wild and various they are. Rumps of sand that disappear and reappear with the moon, places penguins swim protected by snipers, and a tiny peninsula where a bad current brings a fresh tide of used syringes every night can all be called a Harbour beach.

Paradoxically, some can still be called secret even when they are famous, because they are layered with identities, and part-hidden by their urban setting. One, on the lip of Point Piper, is extra well-known for these cross-purposes. It has aliases. “Murray Rose Pool” and “Seven Shillings Beach” are the same place, but in real life no-one calls them anything other than Redleaf, or Redleaf Pool. Other tidal pools in the city share some of its features – the wooden pontoons and diving platforms, and the iron bars to keep out sharks. But at Redleaf they are arranged differently, at the bottom of a steep, tiered garden, that frames them like a Northern Hemisphere lido or lakeside pool.

This design caused a minor controversy before Redleaf opened in the late summer of 1941, and aldermen had to be assured it would look more Australian than European (“a Yugoslav with special knowledge” had assisted the architect). Soon it was so popular with post-war refugees and migrants that it was nicknamed “Refleaf”. There were occasional tensions early on—an argument over Greeks dancing and playing a harmonica turned into a fifty man brawl—but for the most part, newspapers lingered over stand-offs between beach inspectors and improperly dressed women. A Daily Telegraph headline reading “FRENCH GIRL TOLD TO LEAVE POOL” was typical, and this status as a site of cosmopolitan, libidinal interest was set both immediately and permanently.

It was during this period that Oliver Watts’s grandfather, Janek Szczecinski, would frequent Redleaf every day. He browned his skin with coconut oil, and wore a Swiss ingot necklace that nestled in his chest hair, and went there not to swim but to hit a tennis ball against a wall with a net painted on it. He is not depicted in these paintings, but his spirit is – Jewish masculinity ripened by the sun, Old Europe becoming New Australian. That lineage also reflected in Oliver’s media, acrylic paint on an extra fine grain canvas which dries matte to the point of harshness. It is the material of Pop Art and vigorous amateurs, and when depicting posed bathers, it becomes a 20th century route to the 19th, Courbet via David Hockney.

These works are informed and art historical, but not sagging with allusions. Instead, they are exuberant and jokey – there is a Sappho on the cliff in Speedos. They are innovative, especially with the palette (though Ollie actually uses a plate). Look at that sky, water and shadow – anyone who has nursed a hangover through to sunset on this dirty sand knows those afternoon violets, coppers and greens. This bunnies-and-hearts camouflage pattern in livid pastels is responsive and rich enough that you can almost hear the obnoxious, echoing music from a moored pleasure craft in the middle distance. It’s a style that has become one of Ollie’s signature achievements, like writing a glittering novel in comic sans.

Any contemporary Australian beach art has to reckon with Charles Meere, whose Beach Pattern helped reorientate national identity from the bush to the surf. The location in that work is unidentified or unreal (Meere never went to the beach), but its thrusting posers, one of whom is ready to whack a beach ball, must be somewhere on the coast. The honed, white physiques of Meere’s formalist figures are cryptic, even sinister (they have been called the “iconic example of ‘Aryan’ hedonism in Australian life”), and the subsequent attempts to subvert it have often reproduced it, with varying doses of irony and multiculturalism.

At Redleaf is a different counterweight to healthy minds and healthy bodies. This is the territory of the night swim and the skinny dip, the come down and the after party. As Ollie started to paint this series, friends shared their own secrets. Redleaf was a favourite Tinder date spot for many. There were stories, queer and straight, of liaisons on the pontoons and in the sand. One night-time gathering ended with a search party when a reveller went missing leaving only his clothes left behind. Feared drowned, he was found huddled in the doorway of his Potts Point apartment, after walking up on William Street, naked.

One man recounted his first date with the woman who would become his wife. They walked down the hill in the dark and to the water’s edge, where he pissed in the pool to stir up the phosphorescence and draw it to the surface. It’s a distinct analogy for the paintings, and the same kind of pleasure.

-Richard Cooke, 2023

See Full Exhibition Catalogue HERE